Illegal dismissal of employees

It is established that discipline of employees is part of management prerogative. But when the disciplinary action amounts to dismissal or termination of an employee, the Labor Code provides stringent rules that must be complied with. Otherwise, the termination of the employee is considered illegal.

To start, the dismissal must comply with Substantive Due Process, which means that the dismissal of an employee must be for a just cause or authorize cause. Thus, the employer cannot just dismiss an employee out of whim.

The following are the Just Causes under the Labor Code:

-

Serious misconduct or willful disobedience by the employee of the lawful orders of his employer or representative in connection with his work;

In willful disobedience, the following requisites must concur:

- The employee’s assailed conduct must have been willful or intentional, the willfulness being characterized by a “wrongful and perverse attitude; and

- The order violated must have been reasonable, lawful, made known to the employee and must pertain to the duties which he/she had been engaged to discharge.

- Gross and habitual neglect by the employee of his duties. Mere neglect is not sufficient. The neglect must be both gross and habitual.

- Fraud or willful breach by the employee of the trust reposed in him by his employer or duly authorized representative. For loss of confidence as a ground for dismissal, the employee concerned must be holding a position of trust and confidence.

- Commission of a crime or offense by the employee against the person of his employer or any immediate member of his family or his duly authorized representative.

- Other causes analogous to the foregoing.

On the other hand, misconduct must be serious for it to be a just cause for termination. Some examples of serious misconduct as a just cause for termination are falsification of time records and immorality.

The following are the Authorized Causes under the Labor Code:

-

Closure of establishment and reduction of personnel

These are labor saving devices, redundancy, retrenchment to prevent losses, closing or cessation of the establishment. If the termination is based on this ground, the employer must serve a written notice to the employees and to the Department of Labor and Employment at least thirty (30) days prior to the intended date of termination.

-

Disease of the employee

The employee must be found to be suffering from any disease and whose continued employment is prohibited by law or is prejudicial to his/her health, as well as the health of his or her fellow employees.

It is not enough that the dismissal is based on a Just Cause or Authorized Cause, Procedural Due Process must also be observed.

The following is the procedure that must be complied with in terminating the services of an employee based on just causes:

- Written Notice must be served on the employee specifying the ground(s) for termination and giving his reasonable opportunity within which to explain his/her side;

- Hearing or conference shall be conducted wherein the employee is given an opportunity to respond to the charge and to present his/her evidence. The employee may be assisted by his/her counsel, if so desires.

- Written notice of termination must be served on the employee indicating that upon due consideration of all the circumstances, grounds have been established to warrant his/her termination.

Entitlement to Separation Pay

It must be pointed out that when an employee is dismissed based on a just cause with compliance with the Procedural Due Process, the dismissed employee is not entitled to the payment of Separation Pay.

The following are the instances when an employee is entitled to the payment of separation pay:

- Installation of labor-saving devices

- Redundancy

- Retrenchment

- Closure or cessation of business operations

- Disease of an employee and his continued employment is prejudicial to himself or his co-employees

- When an employee is illegally dismissed but reinstatement is no longer feasible

Reinstatement and Backwages

Full back wages is inclusive of the allowances and other benefits computed from the time the compensation is withheld from the employee, until the time of his/her reinstatement.

Also, the reinstatement must be to the employee’s former or equivalent position without loss of seniority rights and other privileges.

If reinstatement is no longer feasible, that is the time that the employer must pay separation pay in lieu of reinstatement.

Article 36 - Philippine Family Code

Psychological Incapacity as a ground for the nullifying void marriages is provided under Article 36 of the Family Code, to wit:

Article 36. A marriage contracted by any party who, at the time of the celebrating, was psychologically incapacitated to comply with the essential marital obligations of marriage, shall likewise be void even if such incapacity becomes manifest only after its solemnization.

In the case of Republic vs. Court of Appeals and Molina (G.R. No. 108763, February 13, 1997), the Supreme Court laid down the guidelines for interpreting and applying Article 36. The following are the Molina Guidelines:

- Burden of proof to show the nullity of marriage belongs to the plaintiff;

-

The root cause of the psychological incapacity must be:

- medically or clinically identified;

- alleged in the compliant;

- sufficiently proven by experts; and

- clearly explained in the decision.

- The incapacity must be proven to be existing at the time of the celebration of the marriage;

- Incapacity must be shown to be clinically or medically permanent or incurable;

- Such illness must be grave enough to bring about the disability of the party to assume the essential obligations of marriage;

- The essential marital obligations must be those embraced by Articles 68 up to 71 of the Family Code as regards the husband and wife as well as Articles 220, 221 and 225 of the Family Code;

- The interpretations given by the National Appellate Matrimonial Tribunal of the Catholic Church in the Philippines, while not controlling, shall be given great respects by the courts.

Since the promulgation of the Molina decision in 1997, only a few cases were found to have met the Guidelines laid down in Molina. Thus, in the case of Tan-Andal vs. Andal, the Supreme Court stated that “it is time for a comprehensive but nuanced interpretation of what truly constitutes psychological incapacity.”

Quantum of Proof

In the case of Molina, it is stated that the plaintiff has the burden of proving psychological incapacity, but is silent as to the quantum of proof required. In Andal, the Supreme Court ruled that “the plaintiff-spouse must prove his or her case with clear and convincing evidence.” The reason is that the presumption of marriage can only be rebutted by clear and convincing evidence.

Psychological Incapacity does not mean medical incapacity or equivalent to a personality disorder

In the case of Santos vs. Court of Appeals (G.R. No. 112019, January 4, 1995), the Supreme Court interpreted psychological incapacity as a mental incapacity, and was confined to “the most serious cases of personality disorders clearly demonstrative of an utter insensitivity or inability to give meaning and significance to the marriage”. This interpretation paved the way to treating or identifying psychological incapacity as a mental incapacity and personality disorders.

However, records of the Code Committee shows that psychological incapacity is not intended to be synonymous or equal to a mental incapacity, or to personality disorders. Thus, psychologists and psychiatrists as expert witnesses have become a standard in nullity cases in order to identify the personality disorder of the incapacitated spouse.

In Andal, the Supreme Court categorically abandoned the Molina guideline which required the medical or clinical identification of the psychological incapacity or root cause, and that the same must be sufficiently proven by experts. The Supreme Court emphasized that the psychological incapacity is “neither a mental incapacity nor a personality disorder that must be proved through expert opinion”.

What must be proven is the “durable or enduring aspects of a person’s personality called “personality structure”, which manifests itself through clear acts of dysfunctionality that undermines the family. The spouse’s personality structure must make it impossible for him or her to understand and, more important, to comply with his or her essential marital obligations.”

Expert testimony is not required to prove these aspects of personality, and ordinary witnesses are sufficient as long as they have been present in the pre-married life of the spouses and can testify as to the behaviors that they have consistently observed from the incapacitated spouse.

Juridical antecedence is still required

That the psychological incapacity must be existent at the time of the marriage. This means that juridical antecedence is still required as it is specifically mandated under Article 36. The juridical antecedence may be proven by testimonial evidence on the spouse’s past experiences that led them to their psychological incapacity.

Psychological incapacity must be incurable, but in the legal sense

In Andal, the Supreme Court amended the third Molina guideline by saying that while psychological incapacity must be incurable, the incurability must be in the legal sense, and not in the medical sense. Incurability in the legal sense means that the “incapacity must be so enduring and persistent with respect to the specific partner, and contemplates a situation where the couple’s respective personality structures are so incompatible and antagonistic that the only result of the union would be the inevitable and irreparable breakdown of the marriage.”

Gravity

The requirement that the psychological incapacity must be grave is retained, which must be shown that it is caused by a genuinely serious cause. The Supreme Court clarified, though, that gravity is not in the sense that the psychological incapacity must be shown to be a serious or dangerous illness.

Essential Marital Obligations

In Andal, the Supreme Court ruled that the essential marital obligations are limited to those between the spouses. However, once the spouses have children, their obligations to their children are also a part of their spousal obligations to each other Furthermore, the Supreme Court clarified that not all kinds of failure to meet the obligations to their children will nullify the marriage, but only those that are shown to be of “grievous nature that it reflects on the capacity of one of the spouses for marriage”.

The Supreme Court summarized the amendment, as follows:

“To summarize, psychological incapacity consists of clear acts of dysfunctionality that show a lack of understanding and concomitant compliance with one’s essential marital obligations due to psychic causes. It is not a medical illness that has to be medically or clinically identified; hence, expert opinion is not required.

As an explicit requirement of the law, the psychological incapacity must be shown to have been existing at the time of the celebration of the marriage, and is caused by a durable aspect one’s personality structure, one that was formed before the parties married. Furthermore, it must be shown caused by a genuinely serios psychic cause. To prove psychological incapacity, a party must present clear and convincing evidence of its existence.”

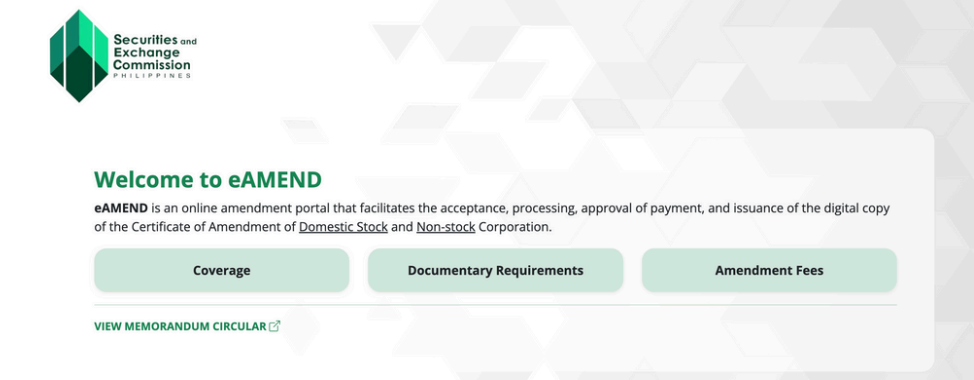

Welcoming One Person Corp.

We have all heard about sole proprietorships. Most small business are under a sole proprietorship setup too. It’s quick, easy, and hassle-free. But with the amendment of the Corporation Code, comes now the One Person Corporation (OPC). Is there a difference between the two?

Before, there were only three business forms—sole proprietorship, partnership, and corporation. However, in 2019, RA 11232 was signed into law, revising the 38-year-old Corporation Code, to improve the ease of doing business in the country. One of the new provisions under RA 11232 concerns OPC.

Essentially, a sole proprietorship is a form of business organization with only one proprietary owner; a single individual who conducts business under his own name or an assumed trade name. The single proprietor is personally liable, and at the same time, he personally owns all the assets of the business.

On the other hand, an OPC has a legal personality that is separate and distinct from the sole stockholder of the corporation. The OPC, despite what the term “One Person” suggests, does not violate the concept of separate and distinct personality of corporations. If such is alleged, the burden is on the person to prove that the OPC is financially equipped and sustainable. The assets of the OPC are not owned by its sole stockholder, unless the OPC is not adequately financed. Likewise, the obligations of the corporation cannot be enforced against its sole stockholder, unless the situation would warrant the piercing of the veil of corporate fiction.

Under the Revised Corporation Code, a shareholder can now purchase all the shares of an existing corporation. Subsequently, he may apply for “conversion” and establish the OPC. Moreover, the OPC does not need to change its registration or disturb continuity of its life. It can convert and subsequently receive investors or admit strategic partners. All the OPC needs to do is to amend its Articles of Incorporation (AOI) and to follow the required governance for a regular corporation.

There is also no minimum paid-up capital required when it comes to an OPC, unlike in regular corporations. The OPC only needs to declare its proposed authorized capital stock, subscribed and paid-up, unless special laws or other rules would require it to do so, based on its intended operations.

It should be kept in mind that, in an OPC, it is required to appoint a nominee and an alternate nominee. The nominee will temporarily take the place of the one person until the interest of the one person is transferred to his lawful heirs, in case he dies abruptly.

For more information, you may visit the website of the Securities and Exchange Commission at www.sec.gov.ph.

Register a land in your name

Almost everyone dreams of investing and having their own property. Filipinos, more often than not, were raised to dream of being able to have their own, one day. This is dictated by our culture of hard work and making our family proud.

Acquiring properties in the Philippines may be easy if you know the process and if you have the required documents. This starts with the Deed of Sale between the buyer and the seller. The Deed of Absolute Sale contains the details of the buyer and seller (e.g., TIN), the price of the property, the technical description of the property, along with other provisions relating to the sale.

The Deed of Absolute Sale evidences the transaction between the buyer and seller. Before or upon signing the Deed of Absolute Sale, the seller should also provide the buyer his Owner’s Duplicate Copy of the Transfer Certificate of Title (TCT), as well as the certified true copies of the latest Tax Declaration. If the property sold is a vacant lot or no improvements have been made on it, a sworn declaration of no improvement must be executed. A Certificate of No Improvement may also be requested from the City or Municipal Assessor. To the best interest of the buyer and to confirm the legitimacy of the sale, he must also visit the subject property before proceeding with the sale.

Having the Deed of Absolute Sale does not automatically transfer the title of the subject property to the buyer. The buyer must now proceed to the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR), which will assess the taxes, such as the Capital Gains Tax (CGT) and Documentary Stamp Tax (DST). Such taxes must be paid.

The buyer must return to the BIR to claim his Certificate Authorizing Registration (CAR/eCAR), which will be released with the following documents: a) Original copy of the Deed of Absolute Sale, with the stamp of the BIR; b) Owner’s duplicate copy of the TCT/CCT; c) Original copies of the BIR forms stamped by the BIR; d) Copies of the Tax Declaration.

The buyer must pay the transfer taxes and secure the tax clearance at the local treasurer’s office. Subsequently, he shall file the pertinent documents with the Registry of Deeds for the issuance of a new land title. The new owner’s duplicate copy of the TCT and CCT will be released once the buyer has presented his documents such as the Deed of Absolute Sale, CAR, Tax Clearance, current Tax Declaration, and official receipts of payments of CGT, DST, Tax Clearance Certificate, and Transfer Fee.

He must then file the same documents with the Municipal or Provincial Assessor’s Office for the issuance of a new Tax Declaration. It must be emphasized that the buyer must first go to the Registry of Deeds for the acquisition of a new land title before he proceeds to the Municipal or Provincial Assessor’s Office, because the name on the land title must coincide with the name indicated on the Tax Declaration.

At present, the Land Registration Authority (LRA) has been implementing the Voluntary Title Standardization Program, which provides title owners to upgrade manually-issued titles to “eTitles”, issued by the LRA’s new Computerized System.

Management Prerogative

Since time immemorial, it has been clear that the labor sector has a constitutionally guaranteed right, pursuant to Sec. 3 of the 1987 Constitution. It provides for full protection to labor, local and overseas, organized and unorganized, and promotes full employment and equality of employment opportunities for all. It also guarantees the right of the workers to certain activities such as self-organization and collective bargaining, as well as the right to strike. These rights are enjoyed by the labor sector, and, in the same vein, the law favors workers too.

However, does this mean that the employer or the management does not have rights and cannot do anything at all?

The answer is no. An employer, in certain instances and within the bounds of law, may exercise its management prerogative in its employee relations.

The Supreme Court held in St. Luke’s Medical Center, Inc. v. Maria Theresa V. Sanchez (G.R. No. 212054, 11 March 2015), that management prerogative is the right of an employer to regulate all aspects of employment. It gives the employers the freedom to regulate, according to their discretion and best judgment, all aspects of employment, including work assignment, working methods, processes to be followed, working regulations, transfer of employees, work supervision, lay-off of workers and the discipline, dismissal, and recall of workers.

In this light, courts often decline to interfere in legitimate business decisions of employers. In fact, labor laws discourage interference in employers’ judgment concerning the conduct of their businesses.

Among the employer’s management prerogatives is the right to prescribe reasonable rules and regulations necessary or proper for the conduct of its business or concern, to provide certain disciplinary measures to implement said rules and to assure that the same would be complied with. At the same time, the employee has the corollary duty to obey all reasonable rules, orders, and instructions of the employer; and willful or intentional disobedience thereto, as a general rule, justifies termination of the contract of service and the dismissal of the employee.

While the law favors the labor sector, this does not necessarily mean that employers are precluded from managing their businesses, including employees, as they see fit. So long as the exercise of management prerogative does not violate employee’s rights and other prevailing laws, the employer shall not be liable for his acts that are intended to maintain his company.

The employer-employee relationship is one that is of a complex nature and requires both parties to coexist harmoniously. Ultimately, they mutually benefit from such relationship. If disrupted and a case is filed by the employee against the employer, it could take a while before the case gets resolved. As such, to avoid litigation, both parties must observe their obligations to each other and must comply with what is provided under the law.

Expats applying for a working visa

The Philippines has been in the top 10 best tourist destinations for quite some time now, due to its pristine beaches, history, and people. The country has attracted foreigners over and over, and some of them have even decided to stay for work. Just like any other country, the Philippines has its own specific requirements and guidelines for foreigners who intend to stay for work. These foreigners are often tagged as “expats”, which means a person who lives outside their native country.

Visa application, anywhere in the world, requires a lot of documents. Sometimes, even if it is just for tourism purposes, numerous documents are required by countries and the applicant undergoes strict scrutiny before a visa is approved or granted.

Visas in the Philippines are divided into three main categories: a) Immigrant Visa; b) Non-immigrant Visa; and c) Special Visa. If a foreigner intends to work in the Philippines, he would fall under the second category, Non-immigrant Visa, specifically the Pre-arranged Employee Visa (PAEV). PAEV is also more commonly known as the 9G.

Foreign nationals who intend to engage in any lawful application, whether for wages or salary or other form of compensation should apply for a PAEV. The foreigner must proceed to the Bureau of Immigration (BI) to apply for one. He may also apply with other immigration offices in the country, and not necessarily with the BI’s main office in Manila.

Some of the documents that need to be submitted are the following:

- Joint letter request addressed to the Commissioner from the applicant and the petitioner

- Duly accomplished CGAF for Non-immigrant Visa

- Photocopy of passport bio-page and latest admission with valid authorized stay

- Photocopy of Employment Contract, Secretary’s Certificate of Election, Appointment or Assignment of applicant, or equivalent document, with details of exact compensation, duration of employment and comprehensive description of the nature and scope of the applicant’s position in the company

- Photocopy of Alien Employment Permit (AEP) issued by the DOLE, and actual publication of the applicant’s approved AEP or in the absence thereof, a Certificate of Publication issued by the Publisher

The foreign national must also submit his application form, and if he has children, he will also need to provide additional information in relation to them.

He must secure the CGAF from the Public Information and Assistance Unit (PIAU) at the Bureau of Immigration or obtain it from the Bureau’s website. Afterwards, he must submit the required documents for pre-screening at the Central Receiving Unit (CRU) of the Bureau. If he intends to submit his documents to other BI offices instead, he may hand it over to the frontline officer of that office.

The foreign national shall also pay the required fees and submit a copy of the official receipt. Fees for visa application ranges from Ten Thousand Pesos (Php10,000.00) to Thirty Thousand Pesos (Php30,000.00). Subsequently, he must attend the scheduled hearing. His fingerprint will then be captured for record at the Alien Registration Division, wherein he should also submit the requirements for ACR I-Card application.

He may check the website of the Bureau to monitor whether his visa application is already approved or call the Bureau’s hotline for follow-up. If the visa application is approved, his passport must be forwarded to the Bureau for visa implementation. Likewise, if his ACR I-Card is approved, he may already claim the same.

For more information, you may visit the website of the Bureau of Immigration at https://immigration.gov.ph/visa- requirements/non-immigrant-visa/pre- arranged-employment-visa.

Knowing more about Data Privacy

In this day and age, the use of technology has been utilized beyond our wildest imagination. We may or may not have foreseen that the internet will be as beneficial as it is now, but it seems that it has found a way to be an essential part of our lives. When Covid- 19 hit the globe, more and more people have also started to make use of the internet, such as to help their businesses—unfortunately, at times, some people also use the internet to take advantage of people’s rights.

Some internet platforms would require a person’s basic information. Usually, this will include a person’s full name, address, contact details, and at times, even photos. While there is a privacy agreement that comes with these forms, no one bothers to read it because of its length. Worse, there are times when these information gets leaked, and in that instance, one should at least have a basic grasp of how he can take caution and protect himself from people with ill intent.

Republic Act No. 10173, more commonly known as the Data Privacy Act of 2012, aims to protect all forms of information, whether private, personal, and even sensitive ones. It covers not just natural persons but also juridical ones, who are involved in the processing of personal information. When we speak of “processing”, this means that the personal information is collected, recorded, stored, or used for some other purpose.

While Data Privacy Act of 2012 seeks to protect all forms of information, there are a number of instances where it cannot be applied, such as but not limited to the following:

- Personal information processed for journalistic, artistic, literary or research purposes;

- Personal information originally collected from residents of foreign jurisdictions in accordance with the laws of those foreign jurisdictions, including any applicable data privacy laws, which is being processed in the Philippines;

- Information necessary for banks and other financial institutions under the jurisdiction of the independent, central monetary authority or Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas to comply with RA 9510 and RA 9160, as amended, otherwise known as the Anti- Money Laundering Act and other applicable laws.

A person filling out a form, whether online or in actual, can only do so much. Companies and organizations must also know their obligations under the law.

Under the Implementing Rules and Regulations of the Data Privacy Act of 2012, all organizations are required to appoint a Data Protection Officer (DPO). The DPO shall be knowledgeable when it comes to data privacy and protection, and he must ensure that the organization or the company is always in compliance with data protection laws.

If and when you feel like your right to data privacy has been violated, whether your personal information has been leaked, or has been misused, or even improperly disposed, you may file a complaint with the National Privacy Commission (NPC). If the NPC finds merit in your complaint, the case will then be forwarded to its Enforcement Division of the Legal and Enforcement Office, for the enforcement of civil damages and fines. Other administrative sanctions may also be upheld, when deemed appropriate.

The NPC may also decide whether the case should proceed to criminal litigation. If it does, it shall forward the case records to the Department of Justice (DOJ) and recommend the prosecution of the case.

Ultimately, whether we are using the internet to provide our personal information or giving it manually, we shall always be careful and cautious with the information we share, and to whom we share them with.

All about Estate Tax

When our loved ones die, we go into a deep grief. Most of the time, we are at a loss for words. Whether the person has properties left behind, safe to say, succession and inheritance are the least of our worries. However, in some instances, we simply cannot keep on avoiding the paperwork that comes with a loved one’s passing. This includes probate of a will, if there is any, and payment of estate taxes.

What is estate tax?

Estate tax is a tax levied, assessed, collected and paid upon the transfer of the net estate of every decedent, whether resident or nonresident of the Philippines, to the heirs, based on the value of such net estate, by including the value at the time of his death of all property, real or personal, tangible or intangible, wherever situated.

However, in the case of a nonresident decedent, who at the time of his death was not a citizen of the Philippines, only that part of the estate which is situated in the Philippines shall be included in his taxable estate, as computed in accordance with the estate tax rate imposed under Sec. 84 of the NIRC of 1997, as amended.

In essence, estate tax is a type of excise or privilege tax, because it aims to tax a privilege—that is, of shifting the economic benefits and enjoyment of property from the dead to the living. It is not a tax against the property of a decedent, nor is it a claim against the estate. It is simply the tax on the right to succeed to, receive, or take property by either testamentary or intestate succession. It must be remembered that the right to succeed is likewise not a natural right, but one that is provided by the statute. It is, just like estate tax, a privilege.

Estate tax accrues on the date of the death of a person. However, accrual of the tax is distinct from the obligation to pay the same. Upon the death of the person, succession instantly takes place and the right of the State to tax the privilege to transmit the estate vests instantly as well, upon his death.

What are the items included in determining the Gross Estate of a decedent?

Under prevailing law, the items to be included are the following:

- decedent’s interest

- transfer in contemplation of death

- revocable transfer

- property under a general power of appointment

- proceeds of life insurance

- prior interests

- transfer for insufficient consideration

- claims against insolvent persons

- unpaid mortgages

- family home

Are there exclusions from the Gross Estate?

Yes. Some of these include but are not limited to the following:

- GSIS and SSS benefits, accruing by reason of death;

- amounts received by veterans from the PH and US government, from the damages suffered during WWII;

- property outside the Philippines of a nonresident alien;

- capital or exclusive property of the surviving spouse.

Filing and Payment of Estate Tax

Previously, it was required to file a Notice of Death. However, this was already repealed and is no longer required at present. Estate tax is required to be filed in all cases of transfers, subject to estate tax. It is also required regardless of the gross value of the estate, where the said estate consists of registered or registrable property. This includes real property, motor vehicle, shares of stock, or other similar property for which a clearance (eCAR) from the BOR is required as a condition precedent for the transfer of ownership thereof, in the name of the transferee, the executor, or the administrator, or any of the legal heirs of the decedent, as the case may be.

It should be noted that TRAIN Law has deleted the clause “or where though exempt from tax, the gross value of the estate exceeds Php200,000.”

The executor, or the administrator, or any of the legal heirs of the decedent must file the estate tax return. If there are none, any person in actual or constructive possession of any property of the decedent may file the estate tax return, pursuant to Sec. 90(A) of the Tax Code.

Effective January 1, 2018, the estate tax rate is set at 6%, based on the fair market value of the taxable net estate at the time of death of the decedent. In May 2021, the House committee on ways and means has recommended that the chamber House approve the Senate’s amendments to House Bill 7068, which would extend the estate tax amnesty application period by two years, or until June 14, 2023.

What is E-commerce?

Online selling has been a thing for few years now. Most businesses have opted to sell their products on the internet to be able to have a wider reach in the market. Since almost everyone has access to the internet these days, it is easier and quicker to cater to consumers, whether for goods or services.

Products being sold on the internet range from household items to even electronic gadgets. Almost everything you need can now be ordered and bought with the help of the internet. Services are also advertised now with the use of social media, and bookings or appointments may also be made through it.

With the happening of Covid-19 and the closure as well as limited hours of establishments, businesses have truly taken advantage of the internet. Considering that certain protocols must be observed as well due to the pandemic, it is only wise to take the business to a different “level”.

In the Philippines, Electronic Commerce Act of 2000 (more popularly known as E-commerce Act) has been in place since 2000. It aims to facilitate domestic and international dealings, transactions, arrangements, and the like, through the use of electronic medium. Under the law, E-commerce Act applies to any kind of data message and electronic document used in the context of commercial and non-commercial activities to include domestic and international dealings, transactions, arrangements, agreements, contracts and exchanges and storage of information.

Some of E-commerce Act’s salient features are the following:

- Empowers the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) to supervise the development of e-commerce in the country. It can also come up with policies and regulations, when needed, to facilitate the growth of e-commerce.

- All existing laws such as the Consumer Act of the Philippines also applies to e-commerce transactions.

- It gives legal recognition of electronic data messages, electronic documents, and electronic signatures.

- Allows the formation of contracts in electronic form.

- Makes banking transactions done through ATM switching networks absolute once consummated.

Under the law, certain acts shall be penalized by fine and/or imprisonment, such as: a) hacking or crackling; b) piracy; c) violations of Consumer Act (RA 7394); and d) other violations of the provisions of the Act.

At present, again, due to the pandemic, most government offices have also resorted to the use of the internet. Pre-Covid, some of these government agencies, such as the SEC, have already started using the internet for certain transactions. Courts and quasi-judicial agencies have also likewise started the implementation of e-filings, to prevent the spread of the virus.

In 2020, DTI has expressed its support for various bills related to e-commerce, such as House Bill 6122 or the Internet Transactions Act. The Bill seeks to establish an e-commerce bureau, which shall focus on promoting the development of e-commerce in the country, as well as establishing trust between sellers and consumers. The Bill also seeks to lay down ground rules for online consumer protection and safer e-payment gateways.

Anti-Violence Against Women and Their Children

Republic Act (RA) No. 9262 or the AntiViolence Against Women and Their Children Act of 2004 allows women and children to enjoy the protection that the law has granted to them from the violence perpetrated by women's intimate partner, i.e., husband; former husband; or any person who has or had sexual or dating relationship with the woman, or with whom the woman has a common child.

The law seeks to define and criminalize acts of violence against:

- Woman who is the wife or former wife;

- Woman with whom the person has or had a sexual or dating relationship;

- Women with whom the person has acommon child;

- Child whether legitimate or illegitimate within or without the family abode.

From the wording of the statute, it can be perceived who may be the offender and offended party. Nonetheless, the Supreme Court was faced with an issue as to whether a father may apply for protection and custody orders under RA No. 9262 on behalf of his minor child against the mother who is alleged to have committed violence against their child.

It must be noted that prior to the case of Knutson vs. Sarmiento-Flores (G.R. No. 239215, July 12, 2022), the case of Ocampo v. Arcaya-Chua (A.M. OCA IPI No. 07-2630- RTJ,April 23, 2010) identified persons who are classified as offender and offended parties. Under RA No. 9262, offender refers to any person who is the husband, former husband, those who had sexual or dating relationship with the woman or with whom she has a common child while offended party may be the wife, former wife, a woman who has or had sexual or dating relationship, or with whom the man has a common child or her child. From the foregoing, it was concluded that the definition of an offender does not include the child’s mother. Thus, a child’s mother cannot be considered as an offender under RA 9262.

However, in the landmark decision dated July 12, 2022, the Court’s En Banc, through Associate Justice Mario V. Lopez, upheld the right of a father under RA No. 9262 to apply for protection and custody orders against the mother who committed violence against their child. Emphasizing that the issuance of Temporary Protection Order (TPO) is principally and directly for the protection on behalf of the minor child and not the father.

Court records show that an American citizen Randy Michael Knutson filed, on behalf of minor Rhuby Sibal Knutson, a petition under RA 9262 for the issuance of Temporary and Permanent Protection Orders against Rosalina Sibal Knutson before the Regional Trial Court of Taguig City, Branch 69 (RTC) alleging that the mother placed their daughter to an environment harmful to the daughter’s physical, emotional, moral, and psychological development.

The lower court dismissed the petition citing the ruling in Ocampo vs. Araya-Chua that a protection order cannot be issued in favor of a husband against his wife. It further said that the remedies under RA No. 9262 such as the issuance of a Temporary/Permanent Protection Order are not available to the father because he is not a “woman victim of violence”. A Motion for Reconsideration was filed by petitioner Randy but it was denied by the RTC reiterating that RA No. 9262 does not apply to situations where the mother committed violence against her own child.

The Supreme Court held that RA No. 9262 covers a situation where the mother committed violent and abusive acts against her own child. The Court emphasized that the statute used the gender-neutral word “person” as the offender which embraces any person of either sex, thus, it does not single out the husband or father as the culprit.

The Court further held that Section 9(b) of RA 9262 explicitly allows “parents or guardians of the offended party” to file a petition for protection orders. Here, the statute used “parents” which pertains to the father and the mother of the woman or child. In the instant case, the offended party is Rhuby, a minor child, who experienced violence and abuse. Randy merely assists Rhuby in filing the petition as the parent of the offended party. Likewise, Randy is not asking for a protection order to be issued in his favor but rather on behalf of their minor daughter Rhuby. The Court highlighted that the best interest of the child should be the primordial and paramount concern.

“Obviously, the RTC's restrictive interpretation requiring that the mother and her child to be victims of violence before they may be entitled to the remedies of protection and custody orders will frustrate the policy of the law to afford special attention to women and children as usual victims of violence and abuse. The approach will weaken the law and remove from its coverage instances where the mother herself is the abuser of her child. The cramping stance negates not only the plain letters of the law and the clear legislative intent as to who may be offenders but also downgrades the country's avowed international commitment to eliminate all forms of violence against children including those perpetrated by their parents” the Court said, highlighting the discriminatory interpretation of the RTC in denying the petition.

CLERICAL ERROR LAW (R.A. NO.9048, AS AMENDED BY RA 10172)

Remedial Law; Special Proceedings; RA 9048; RA10172

MARYROSE A. RIOS

ANY PERSON WHO HAS A DIRECT AND PERSONAL INTEREST IN THE CORRECTION OF A CLERICAL OR TYPOGRAPHICAL ERROR OR MISTAKE IN CIVIL REGISTER

where it is patently clear that there is a clerical or typographical mistake in the entry and wishes to:

- Change his or her first name;

- Correct clerical or typographical errors in the civil register;

- Change/correct the day and/or month of his or her date of birth; or

- Change/correct his or her sex

He or she must file a verified petition with the local civil registry office of the city or municipality where the record being sought to be corrected or changed is kept (Sec. 3, RA 9048)

Because of the enactment of RA 9048, the remedy and the proceedings for change of first name now dispensed with the need for judicial proceedings. Thus, a person may now change his or her first name or correct clerical errors in his/her name through administrative proceedings and the jurisdiction over applications for the same is now lodged to the administrative officers.

Under Section 2 of RA No. 9048, the law defined clerical or typographical error as a mistake committed in the performance of clerical work in writing, copying, transcribing or typing an entry in the

in the civil register that is harmless and innocuous, such as misspelled name or misspelled place of birth or the like, which is visible to the eyes or obvious to the understanding, and can be corrected or changed only by reference to other existing record or records.

However, corrections involving change of nationality, age, status or sex of the applicant are not allowed under this law. Hence, the remedy of the applicant is to file a petition for cancellation or correction of entries under Rule 108.

In the case of Bartolome vs. Republic (G.R. No. 243288. August 28, 2019), the Supreme Court discussed a test to determine whether a correction is clerical or substantial cancellations or corrections under Rule 108 of the Rules of Court. The court held that misspelled names or missing entries are clerical corrections if the following are present:

- They are visible to the eyes or obvious to the understanding and

- They may be readily verified by referring to the existing records in the civil register.

- It does not involve any change in nationality, age or status.

In Republic vs. Gallo (G.R. No. 207074. January 17, 2018), the Court unequivocally held that a prayer to enter a person's middle name is a mere clerical error, which may be corrected by referring to existing records. Thus, it is primarily administrative in nature and should be filed pursuant to R.A. 9048 as amended.

Grounds for Change of First Name or Nickname

RA No. 9048 expressly enumerated the grounds for change of first name or nickname, to wit: The petitioner finds the first name or nickname to be ridiculous, tainted with dishonor or extremely difficult to write or pronounce. The new first name or nickname has been habitually and continuously used by the petitioner and he has been publicly known by that by that first name or nickname in the community: or The change will avoid confusion. (Sec. 4, RA 9048)

When the Court was faced with the question as to whether change/correction sought in the petitioner's first name, as appearing in his birth certificate, from “Feliciano” to “Ruben” be filed under RA 9048, Rule 103 or Rule 108 of the Rules of Court, the Court ruled that since the petitioner seeks to change his first name on the ground that he has been using the name “Ruben” since childhood, the change that the petitioner sought is covered by RA 9048 and should have been filed with the local civil registry of the city or municipality where the record being sought to be corrected or changed is kept. (Bartolome vs. Republic).

IDENTITY THEFT IN THE PHILIPPINES

DANJEN JINAYON

Introduction

The emergence of the Digital Age has

paved the way for a more

comprehensive implementation of

technology in everyday life, from

payment methods to identification

cards to shopping and even banking,

to name a few. Despite its aim of a

better and easier life, technology

usage has also increased its user's

vulnerability. Identity theft is one of

the most common and awful kinds of

cyber crimes. It involves the

unauthorized use or acquisition of

one's personal information for

fraudulent activities.

Identity theft victims can suffer financial losses, damage to their reputations, and even emotional distress. The Philippines recognizes the risks that this crime can pose to the victims, which has led to the implementation of two laws that aim to govern Filipinos against the threat of Identity Theft, namely, the Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012 and the Data Privacy Act of 2012.

Legal Framework

Under the Republic Act No. 10175, also

known as the Cybercrime Prevention

Act of 2012, identity theft is the

intentional acquisition, possession,

alteration, use, misuse, or deletion of

identifying information belonging to

another person. Victims of identity

theft are advised to file a report to the

authorities and seek damages for their

losses. To do so, victims must file a

civil lawsuit against the perpetrator.

Penalties can vary from a fine of two

hundred thousand (200,000) to

imprisonment

On the other hand, under the Data Privacy Act of 2012 (R.A. 10173), individuals found guilty of unlawful possession and processing of personal information can be fined a minimum of five hundred thousand (500,000) and a maximum of seven years (7) in prison.

Actions To Protect Yourself

Understanding Identity theft is a way to prevent yourself from being a victim. To address

this growing problem, here are some ways you could do to protect yourself:

1.Be careful when giving out your personal information to different social platforms.

Websites, emails, as well as chat and community groups, are just one of the many

platforms where identity theft perpetrators lure their victims. They may pretend to be

someone else, send clickbait, and even provide sob stories to get you.

2. Read and understand privacy statements. Before you can access websites or

applications, these pop-ups inform you how they collect and store your data. Make sure

that you agree to their terms before you accept it.

3. Allow two-factor authentication. 2FA is a security system that will require you to have

two separate and distinct forms of identification to access your account. Generally, the

first factor will be your password, whereas the second factor may include biometrics,

one-time pin (OTP), face identification, and even retina.

4. Use a strong password, and always keep your password up to date. Remember that

the more complex your password is, the more it'll make it difficult for perpetrators to

access your information.

5. Do not open unreputable websites when making a purchase. There are a variety of

potential threats to accessing unsecure websites, including stealing sensitive information,

redirecting to malicious sites, altering data, and cyber attacks.

Conclusion

In conclusion, identity theft significantly threatens individuals, institutions, and the overall

security landscape. In exchange for the ease of the digital age, technological

advancement has also made it easier to exploit vulnerabilities. Preventative measures,

such as stringent data protection laws, increased cybersecurity measures, and public

awareness campaigns, are crucial in combating this pervasive issue

PERSON/S LIABLE FOR CYBER LIBEL

Atty. Maryrose A. Rios

Criminal Law; Libel; Cyberlibel; Internet; Social Media

With the growing number of social media users,social media became one of the primary tools of communication in the Philippines.In the Philippines,as of January 2023, there are 84.45 million social media users or 72.5 percent of the total population, 116.5million to be exact.

However, when people started to fully take advantage of this tool, it has, at the same time, paved the way to new forms of criminal activities which exposes people to criminal liabilities. Cyber libel is among the common criminal acts that people commit.

In this article, we will determine when social media users will be held liable for the crime of cyber libel. If a person posted, commented, shared, or liked a libelous post on social media, will they be held liable under this law?

To start, cyber libel in the Philippines is governed by the Republic Act No. 10175 or the Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012. Although the said law does not really provide a definition of cyber libel, it penalizes libel, as defined under the Revised Penal Code (RPC), but imposes one (1) degree higher than that provided for by the RPC because of the use of information and communication technologies (Section 6, RA 10175).

Definition of Libel

Under Article 353 of the RPC, the

Code define libel as follow:

Art. 353. Definition of libel. — A

libel is public and malicious

imputation of a crime, or of a vice

or defect, real or imaginary, or

any act, omission, condition,

status, or circumstance tending

to cause the dishonor, discredit,

or contempt of a natural or

juridical person, or to blacken the

memory of one who is dead.

How Libel is Committed

A libel is committed by means of any of the following:

- Writing

- Printing

- Lithography

- Engraving

- Radio

- Photograph

- Painting

- Theatrical Exhibition

- Cinematographic Exhibition or any similar means(Art. 355, RPC)

How Cyberlibel is Committed

The RA 10175 provisions on libel read:

The unlawful or prohibited acts of libel as defined in Article 355 of the Revised Penal Code, as amended,

committed through a computer system or any other similar means which may be devised in the future. (Sec.

4(c)(4), RA 10175)

Elements of Cyberlibel

The following are the elements of cyber libel based on Section

4(c)(4) of R.A. 10175, in relation to Articles 353 and 355 of the

Revised Penal Code:

- There must be an imputation of a crime, or of a vice or defect, real or imaginary or any act, omission, condition, status, or circumstance;

- It must be done or made publicly

- There must be an existence of malice The identity of the person defamed whether natural or juridical person or one who is already dead;

- The imputation must tend to cause the dishonor, discredit, or contempt to the person defamed;

- The imputation must be done through the use of a computer system or any other similar means which may be devised in the future.

Original Author

RA 10175 establishesthat the Original Author of the Post isliable to any defamatory statements posted online.

Definition of Original Author

It refers to the person who created or is the origin of the assailed electronic statement or post using a computer

system (Sec. 3[dd], Rule 1, in relation to Sec. 5 [3], Rule 4, Implementing Rules and Regulations of Cybercrime

Prevention Act)

Section 5[3], Rule 4. “xxx Provided, That this provision applies only to the original author of the post or online

libel, and not to others who simply receive the post and react to it.”

Liker/Sharer

In the case of Disini vs. Secretary of Justice, et al (G.R. No. 203335, February 11, 2014), the Supreme Court has

provided illustration to answer the question as to whether “Online Postings”, “Liking”, “Commenting” or

“Sharing” openly defamatory statements are punishable under the law.

For instance, XXX posted on Facebook that “YYY is a thief”. AAA commented that “I like this!; BBB commented

“Correct”; CCC liked the post and DDD shared the post of XXX. Discuss the liability of XXX, AAA, BBB and DDD

liability.

Based on the Disini Case, XXX is liable for the crime of cyber libel because he is the author of the post; AAA is not

liable because he is not the author of the post; CCC is not liable because he is merely expressing his agreement

with the statement on the post, thus, he is still not the author; and DDD is not likewise liable because once again

he is not the author.

“Except for the original author of the assailed statement, the rest (those who pressed Like, Comment and Share)

are essentially knee-jerk sentiments of readers who may think little or haphazardly of their response to the

original posting.”, the Supreme Court said.

From the letter of the law, persons who shared and liked a libelous post are not covered by RA 10175, thus, cannot

be held liable.

Commenter

However, a commenter to the original post who does not merely react to the original post but create or made a

new defamatory statement can be held liable for cyber libel because it is now considered as an original posting

published on the internet. (Disini vs. Secretary of Justice)

Both the Revised Penal Code and the Cybercrime Law clearly punish authors of defamatory publications. Thus,

think before you click.

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS

DANJEN JINAYON

Intellectual property has become a legal and economic concern in the dynamic landscape of the

Philippines. Intellectual property protection has risen over time as the country progressed in creativity,

technology, and commerce. The Republic Act No. 8293, or the Intellectual Property Code of the

Philippines, is designed to grant intellectual property protection to scientists, inventors, artists, and

gifted individuals on their creations.

The IP Code highlights several aspects that are protected under the Philippine Law:

Copyright

The IP code gives creators or authors exclusive rights over their original works. Copyright protection

extends to authors, artists, and musicians from literary, artistic, and scientific creations. The code grants

rights such as reproduction, distribution, and public performance, allowing creators to control the use

and dissemination of their works. This protection covers the author's lifetime and 50 years after their

death.

Trademarks

Trademarks are vital for brand identity. In the world of commerce, distinctive signs, names, symbols, and

images are used to identify products and services. Under the IP Code, trademark protection can be

established by registration and application filed with the Intellectual Property office. Examination of the

trademark application will follow through, which may take up to seven months; however, if opposition

arises during the process, the application may take longer.

On the other hand, successful trademark registrants will be awarded ten years of trademark validity that

can be renewed after ten years. It is essential to note that maintenance requirements shall also be

complied with to avoid cancellation.

Geographic Indications

Geographic Indications are used to protect and identify products that originate from a specific area with a

certain quality or reputation attributable to its origin. Common products well-known for their GI are

Champagne, Parmesan Cheese, Scotch Whiskeys, and Swiss Watches. The Philippines has recently

progressed its GI protection system, acknowledging potential international GI products such as pili, basey

banig, yakan cloth, etc. The application for GI protection can also be acquired through registration at the

Intellectual Property Office. Along with the application, the registrant must submit a certification from

the government that validates the characteristics of the potential GI.

Industrial Design

This pertains to the visual appearance or aesthetic aspect of a product. Registrants must ensure the

product is unique, new in the market, and does not go against public order, health, or morals to be

eligible. In this sense, designs may vary from lines, patterns, shapes, and surfaces. All of which will

undergo examination. A five-year registration will be given to successful registrants; this can be renewed

for only two consecutive periods of five years.

Patents

Patent registration protects inventors against unauthorized appropriation of their product or process. To

acquire a patent on an invention, it must meet the IPO’s three conditions: it must be new, inventive, and

have industrial applicability. Once the patent is issued, the inventor will have the exclusive right to

choose who can be involved in the production or selling of the product. The patent term will be for twenty

years from the filing date. The patent owner may also sell the invention’s right; in this case, the new

owner will be the patent owner.

Layout Design of Integrated Circuits

Topographies of integrated circuits are commonly used in microchips or semiconductors to perform an

electronic function. The layout design can only be protected if it is proven to be owned by the creator and

is of original design during the time of creation. The term for IP protection is ten years and is not

renewable.

1.Undisclosed Information or Trade Secrets

Trade secrets are recognized as independent Intellectual Property. In this case, unlike patents, trade

secrets are confidential and are strictly between the parties involved. This can be protected through

contractual means such as NDAs or confidentiality agreements. Despite the absence of a specific law to

govern trade secrets, several Philippine laws cover breaches of confidential information. As such,

Undisclosed Information or Trade Secrets

Trade secrets are recognized as independent Intellectual Property. In this case, unlike patents, trade

secrets are confidential and are strictly between the parties involved. This can be protected through

contractual means such as NDAs or confidentiality agreements. Despite the absence of a specific law to

govern trade secrets, several Philippine laws cover breaches of confidential information. As such,

unauthorized disclosure or use of trade secrets or any confidential information protected by a contract

can be penalized

WHICH ONE TO FILE?

Petition for Disqualification vs. Petition to Deny Due Course to

or Cancel a Certificate of Candidacy?

ATTY. MARYROSE A. RIOS

Political Law; Election Law; Remedies

The B.P. Blg. 881 or otherwise known as “Omnibus Election Code of the Philippines”

(OEC) provides two (2) available remedies that may filed against bona fide candidates,

viz: (1) Petition for Disqualification and (2) Petition to Deny Due Course to or Cancel a

Certificate of Candidacy.

PETITION FOR DISQUALIFICATION

Grounds for Disqualification

Disqualification case under Sections 12 and 68 of Omnibus Election Code revolves

around on either:

- Candidate’s sanity or competence;

- Candidate’s possession of a permanent resident status in a foreign country; or

- Candidate’s commission of certain acts of disqualification.

Sanity or Competence Under Section 12 of Omnibus Election Code, any person may be disqualified from becoming a candidate and to hold any office, unless he or she has been given plenary pardon or granted amnesty, if he or she:

- has been declared by competent authority insane or incompetent; or

- has been sentenced by final judgment for subversion, insurrection, rebellion or for any offense for which he has been sentenced to a penalty of more than eighteen months or for a crime involving moral turpitude.

Possession of Permanent Resident Status

If the candidate is a permanent resident or an immigrant to a foreign country, he or she shall not be qualified to run for any elective office under OEC.

However, if the candidate waived his status as permanent resident or immigrant of a foreign country in accordance with the residence requirement provided for in the election laws, he or shall may run for an elective office.

Acts of Disqualification In the same provision, election offenses under the OEC which results to a candidate’s disqualification are as follow:

- Giving money or other material consideration to influence, induce or corrupt the voters or public officials performing electoral functions;

- Committing acts of terrorism to enhance one’s candidacy;

- Spending in one’s election campaign an amount in excess of that allowed by the OEC;

- Soliciting, receiving or making any contribution prohibited under Sections 89, 95, 96, 97 and 104 of the OEC; and

- Violating Sections 80, 83, 85, 86 and 261, paragraphs d, e, k, v, and cc, sub-paragraph 6 of the OEC

If a candidate is declared by final decision of the competent court guilty of, or found by the COMELEC of any of the foregoing acts abovementioned, he or she shall be disqualified from continuing as candidate for public office. If the person has already been elected, he or she shall be disallowed from holding the office. (Section 68 of B.P. Blg. 881)

PETITION TO DENY DUE COURSE TO OR CANCEL CERTIFICATE OF CANDIDACY

Grounds for Petition to Deny Due Course

Under Section 78 of the OEC, a denial of due course to and/or cancellation of a COC is premised on a person’s material misrepresentation of the contents of the certificate of candidacy found under Section 74 of OEC.

For instance, a person who violated the three-term limit is an ineligibility which affects the qualification of a candidate to elective office and the misrepresentation of the same is a ground for a petition to deny due course to or cancel a COC. (Aratea vs. COMELEC, G.R. No. 195229, October 9, 2012)

In the case of Loong vs. COMELEC (G.R. No. 93986, 22 December 1992), respondent Nur Hussein Ututalum filed a petition under Section 78 to disqualify petitioner Benjamin Loong for the office of Regional Vice-Governor of the Autonomous Government of Muslim Mindanao for false representation as to his age.

It must be emphasized that the misrepresentation must be material such as misrepresentation as to the candidate’s age, registration as a voter, residence and citizenship among others. Thus, the remedy under Section 78 cannot be invoked if it involves statements that do not refer to the qualifications of a candidate.

As to whether misrepresentation of profession or occupation on a certificate of candidacy punishable as an election offense under Section 262 in relation to Section 74 of B.P. 881, the Supreme Court ruled that in the negative. Profession or occupation not being a qualification for elective office, misrepresentation of such does not constitute a material misrepresentation. Certainly, in a situation where a candidate misrepresents his or her profession or occupation in the certificate of candidacy, the candidate may not be disqualified from running for office under Section 78 as his or her certificate of candidacy cannot be denied due course or canceled on such ground. (Lluz vs. COMELEC, G.R. No. 172840, June 7, 2007)

Conclusion

To determine which one of the two remedies a person may use, you must first consider the ground before filing the petition. For instance, if the action relates to the candidate’s ineligibility or lacking in quality for the elective position which was declared by a final decision of a competent court or as found by the Commission, you must file PETITION FOR DISQUALIFICATION. On the other hand, if your action is based on false representation of the candidate as to material information in his/her COC such as the candidate’s residency, age, citizenship or any other legal qualifications necessary to run for elective office, you must file PETITION TO DENY DUE COURSE TO OR CANCEL A COC.

EMPLOYER-EMPLOYEE RELATIONSHIP

by Atty. Maryrose A. Rios

Labor Law; Post-Employment; Test to

Determine Employer-Employee Relationship

It is established that the employment status of a person is defined and prescribed by law and not by what the parties decide it to be (Century Properties, Inc. vs. Concepcion, G.R. No. 220978, July 05, 2016). Thus, the existence of employer-employee relationship (EER) cannot be negated by repudiating the same through management contracts.

Settled is that before a case for illegal dismissal can prosper, an employer-employee

relationship must first be established. Thus, prior to filing a complaint before the Labor Arbiter

for Illegal dismissal, it is incumbent upon the party who asserts the existence of EER to prove

the EER by substantial evidence. (Atienza vs. Saluta, G.R. No. 233413, June 17, 2019)

Tests to Determine EER

There are two (2) tests that are recognized by the court in determining the existence of EER,

namely:

1.Four-Fold Test; and

2.Economic Reality or the Two-Tiered Test

1.FOUR-FOLD TEST

To ascertain the existence of an employer-employee relationship, jurisprudence has invariably

adhered to the four-fold test, to wit:

1. the selection and engagement of the employee;

2. the payment of wages;

3. the power of dismissal; and

4. the power to control the employee's conduct, or the so-called "control test."

Among the four tests, the Control Test or “Means-and-Method Control Test” is the most

common important indicator of the presence or absence of an employer-employee relationship.

Under this test, an employer-employee relationship exists where the person for whom the

services are performed reserves the right to control not only the end achieved, but also the

manner and means to be used in reaching that end

B. ECONOMIC REALITY OR TWO-TIERED TEST

In the case of Francisco vs. NLRC (G.R. No. 170087, Aug. 31, 2006), the Supreme Court adds

another test, applied in conjunction with the control test, in determining the employment

relations called two-tiered test, which involves an inquiry into the following:

1.The putative employer’s power to control the employee with respect to the means and

methods by the work is to be accomplished (Control Test); and

1.The underlying economic realities of the activity or relationship (Broader Economic Reality

Test)

The broader economic reality test calls for the determination of the nature of the relationship

based on the circumstances of the whole economic activity. The said circumstances of the

whole economic activity are enunciated in the case of Francisco vs. NRC, such as:

1. the extent to which the services performed are an integral part of the employer’s business;

2. the extent of the worker’s investment in equipment and facilities;

3. the nature and degree of control exercised by the employer;

4. the worker’s opportunity for profit and loss;

5. the amount of initiative, skill, judgment or foresight required for the success of the claimed

independent enterprise;

6. the permanency and duration of the relationship between the worker and the employer; and

7. the degree of dependency of the worker upon the employer for his continued employment in

that line of business.

Under this test, the proper standard of economic dependence is whether the worker is

dependent on the alleged employer for his continued employment in that line of business.

The rule is that where a person who works for another performs his job more or less at his own

pleasure in the manner he sees fit, not subject to definite hours or conditions of work, and is

compensated according to the result of his efforts and not the amount thereof, no employer-employee relationship exists. (Loreche-Amit vs. Cagayan De oro Medical Center, G.R. No.

216635, June 03, 2019)

Overtime pay in the Philippines

By Danjen Jinayon

The competitive and fast-paced business environment has increased the demand for more than eight

hours (8) of the allotted working hours. Fortunately, the Philippine Law recognizes the importance of

overtime work and has established a legal framework to ensure fair compensation for employees

beyond their working hours.

Overtime Calculation

Article 87 of the Labor Code is the primary law governing the country's labor relations and employment

practices. According to the law, employees can work beyond eight hours a day, given that they are paid

for overtime. The compensation will be equivalent to an additional 25% of the employee's regular hourly

rate. Meanwhile, work performed beyond eight hours on a holiday or rest day requires an extra 30% of

the employee's hourly rate during a holiday or rest day.

Eligibility and Exemptions

Overtime pay applies to regular employees. However, there are exemptions as provided in Article 82 of

the Labor Code; these non-eligibles include managerial or supervisory positions, government officials

and employees, field personnel, and specific industry sectors that may have overtime provisions.

Right and Protections

Article 87 also protects the rights of employees in the context of overtime work. It emphasizes that no

employee can be compelled to work overtime unless there is a legitimate reason or in emergencies. This

provision underscores the voluntary nature of overtime, ensuring employees can render additional

hours.

By Danjen Jinayon

On the other hand, for the protection of both parties, record-keeping and documentation of generated

working hours shall be done. Documentation tools may include logbooks, time cards, or digital devices

that record employees' working hours.

Dispute Resolution

In case of a disagreement, the first step is often internal, involving open communication between the

parties to understand the underlying issues. If the resolution is not reached, the next recourse may be to

file a complaint with the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) or the National Labor Relations

Commission (NLRC). These government agencies are crucial in mediating disputes, conducting

investigations, and facilitating settlements. Adherence to prescribed procedures and documentation is

vital for a successful resolution. Legal counsel may also be sought to navigate the complexities of labor

laws and ensure that the rights of both parties are upheld throughout the dispute-resolution process.

Domestic and Foreign Adoption in The Philippines

By Danjen Jinayon

Adoption in the Philippines is governed by the Domestic Adoption Act of 1998 (RA 8552), the Inter-Country

Adoption Act of 1995 (RA 8043), and most recently, the Domestic Administrative Adoption and Alternative Child

Care Act (RA11642) that was created to expedite the adoption process in the Philipines. Therefore, any

adoption applicant undergoes a thorough screening and evaluation process under the National Authority for

Child Care (NACC) to ensure the adoption is in the child’s best interest.

Domestic Adoption

Before the passage of RA11642, the adoption process in the country was well-known for being an exhausting

journey for both the prospective parents and the child, but it is no longer an issue as the law took effect in

January 2022. Under this law, domestic adoption will be administrative and no longer judicial. The law also

created a Regional Alternative Child Care Office (RACCO) under the umbrella of NACC; those seeking to

adopt a child may file a petition in their respective RACCO. In order to qualify, the petition of the prospective

parent must assert that:

1.They are 25 years old;

2.They are in possession of total civil capacity and legal rights and of good moral character;

3.They have not been convicted,

4.They are psychologically and emotionally capable of caring for the child;

5.They are at least sixteen (16) years older than the adoptee;

6.They are financially capable and,

7.They had undergone pre-adoption services.

The prospective parent/s must also accomplish the following requirements for the Adoption to take place:

a)Certificate declaring the child legally available;

b)Child case study report prepared by an Adoption Social Worker;

c)Deed of Voluntary Commitment (DVC);

d)Home Study Report;

e)Certificate of Matching;

f)Petition to Adopt the Child;

g)Pre-Adoption Placement Authority; and

h)Social Case Study Report prepared by the Social Worker

Foreign Adoption

As one of the Hague Adoption Convention ratifiers, the Philippines enacted inter-country adoption through

the Inter-Country Adoption Act of 1995 (RA8040). Inter-country or foreign adoption is still governed by RA

8040; however, under the Domestic Administrative Adoption and Alternative Child Care Act (RA11642), all

functions, duties, and responsibilities of the Inter-country Adoption Board (ICAB) will be transferred to the

NACC. In order to qualify, prospective foreign parents must meet the strict requirements that include, but

are not limited to:

1.Must be at least 27 years old, with a minimum of sixteen (16) and a maximum of forty-five (45) years gap

between the prospective parent and the child.

2.Must come from a country with diplomatic relations with the Philippines, a foreign adoption agency

maintained by the government, and a law allowing adoption.

3.Must meet eligibility requirements from their country.

4.If married, the pair must be at least married for a year.

5.Must not be convicted of a crime involving moral turpitude.

6.Must have the ability to assume parenting responsibilities.

7.Must undergo pre-adoption counseling from an accredited counselor in their country.

The application of prospective parents must also consist of the following documents:

1.Application Form

2.Undertaking Oath

3.Personal Data of Applicants

4.Home Study Report (to be prepared by the Central Authority or an accredited Foreign Adoption

Agency)

5.Birth Certificate of applicants

6.Marriage Contract (if married)

7.Psychological evaluation by a duly licensed psychiatrist

8.Latest income tax return or documents that shows the financial capability of the applicants

9.Character reference

10.Certification from an appropriate government agency that states the applicant’s qualification to adopt

under his/her national law and that the adoptee will be allowed to enter the country custody trial and

reside in the country permanently

11.Acceptance letter from the identified guardian of the child.

Note that the procedure and requirements for adoption in the Philippines vary on a case-to-case basis.

Additional requirements might be required by the National Authority for Child Care to ensure the child's best

interest. Prospective parents are advised to consult a legal practitioner specializing in adoption law.

If you want to learn more about the adoption processes and requirements in the Philippines, connect with

our attorneys today.

CITIZENSHIP RETENTION AND REACQUISITION

By Danjen Jinayon

The advancement in migratory dynamics and the increasing trend of Filipinos establishing lives abroad

prompt a progressive and inclusive approach to Philippine legislation through its Dual Citizenship law. The

Republic Act No. 9225, otherwise the Citizenship Retention and Reacquisition Act of 2003, regulates dual

citizenship status in the Philippines. This law enables former natural-born Filipinos to retain/reacquire the

Philippine citizenship they’d lost when they became a naturalized citizen of another country.

Eligibility

Under RA 9225, dual citizenship is reserved for former natural-born Filipinos. Natural-born Filipinos, as

defined in Article IV of the 1987 Constitution, are:

- Citizens born in the Philippines; and,

- Those born before January 17, 1973, of Filipino mothers who elect Philippine citizenship upon reaching the age of majority (21 years old)

Requirements & Process

The consulate office in your country of residence will require you to complete a form and submit a couple of requirementsto ensure the timely processing of your application or petition. Be advised of the following:

a. Duly accomplished dual citizenship application form

b. PSA Birth Certificate

c. Latest Philippine Passport (if available)

d. PSA Marriage Certificate (if applicable)

e. Death Certificate

f. Divorce Decree or PSA Marriage Certificate with Annotation

on Divorce (if applicable)

g. Naturalization Certificate

h. Foreign Passport

i. Passport-size photographs on white background; and,

j. Other documents to prove that the applicant is a former

natural Filipino

Rights, Responsibilities, and Benefits

Acquiring or retaining your citizenship will also grant you the

same benefits as other Filipino nationals; the only difference is

that you will have the advantage of traveling and living in the

Philippines besides your other country of nationality. Some of

the rights that you will attain once your dual citizenship is

granted are as follows:

1) Right to vote. Being a dual-national means you have the right to vote in both national and local elections.

2) Right to work. You can practice your profession in the Philippines, provided you are licensed/ permitted by